Southeastern Anatolia Project (aka GAP)

John Reynolds (June 30, 2007)

Here’s some more information via e-mail from John Reynolds that may have to do with the sixth bowl too.

Hi everyone, this is a post from the Koinonia House forum that I placed a couple of days ago. I have known about this for a couple of years, but I thought given the prophetic implications of this, all of you would definitely like to know about it… In Christ, John

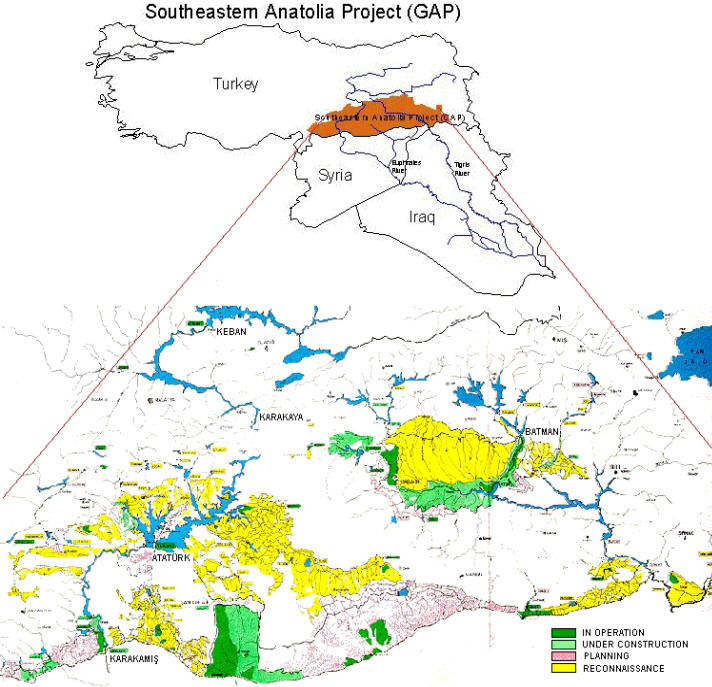

I am not sure if I have posted this yet, but I found out about this a couple of years ago. Turkey has been constructing Dams for a long time and at one point in 1991, in order to fill their reservoirs, they nearly turned off the Euphrates river entirely. In fact, had they wanted to, they could have, but they honored an agreement with Syria to allow X amount of gallons per hour to flow. It is called the Southeastern Anatolia project and it shows how the prophetic river could very easily be dried up to foment the invasion of the 200 million man army... It is also a striking example of another piece of prophecy than can easily be fulfilled at any moment as they already have the capability to do so...SOUTHEASTERN ANATOLIA PROJECT (AKA GAP)

INTRO- http://www.fas.usda.gov/remote/mideast_pecad/gap/introduction.htm

In the 1930s, Mustafa Kamal Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, enacted policies to survey Turkey’s rivers for energy as a means to meet the nation’s growing electricity demands. Gauging stations along the Euphrates and Tigris rivers were established, and geological, topographical, and groundwater surveys were conducted to maximize both the surface and subsurface water resources within the basins. By the 1950s, reconnaissance surveys were extended to Turkey’s 26 different river basins to develop energy and irrigation potential within all river basins.

During the 1960s and 1970s, separate water resources plans to develop the Euphrates and Tigris rivers were drawn, which in 1977 were merged into one water resources development project called the Southeast Anatolian Project. In the 1980s, the Keban and Karakaya Dams along the upper Euphrates river were developed and the Southeast Anatolia Project was later expanded into a multi-sector project that included not only irrigation and hydropower production, but also urban and rural infrastructure, forestry, education, and health sectors. The multi-sector GAP Master Plan was finalized in 1989 and a separate GAP Administration was established. Construction of the Ataturk Dam was completed in 1990 and irrigation for the GAP started at the end of 1994, when one of the twin Sanliurfa Tunnels from the Ataturk Dam was opened.

GAP’s projected completion date is scheduled for 2010, provided current financial difficulties and inflation do not further delay the project. When the GAP is completed, 28.5 percent of the total water potential of the country will be brought under control through facilities along the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers. GAP will irrigate nearly 1.7 million hectares of land, or 20 percent of Turkey’s total irrigable land. Annual energy production from GAP will produce 22 percent of Turkey’s total energy production with an installed energy capacity of 7476 MW.

DETAILED HISTORY (72 PAGES LONG) | 1991 INCIDENT

Syria and Turkey: Many Roots to the Recent Quarrel

Syria and Turkey now say that the agreement signed by them late on October 20 has ended the feud between them, which had led to a Turkish military buildup along the Syrian border (See the Last Issue). The Turks are declaring the agreement a victory for their position, and the beginning of peaceful cooperation with Syria — if Syria fulfills the obligations it has undertaken.

Based on initial reports of the text of the minutes arrived at after two days of negotiations, Syria has agreed that it will provide no support for the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), the Kurdish movement fighting the Turkish government. Arms, logistics, and financial support are all prohibited, and Syria will no longer permit ’Abdullah “Apo” Ocalan, the head of the PKK (See the Profile in the Last Issue) to reside in Syria. Turkish Prime Minister Mesut Yilmaz said that Ocalan had been in Moscow for about a week after leaving Syria during the crisis, and the Turkish press carried reports that he is living in the Moscow suburb of Odintsovo. (Turkey asked Russia to extradite him; Russia said it had no idea where he was.)

The Syrian-Turkish confrontation was unusual in several ways. Though the matters in dispute are of long standing, there was no visible provocation forcing Turkey to act at this time. Rather, the change of Turkish Chief of Staff in August may have been in part the reason for the confrontation now, since new Chief of Staff Hüseyin Kivrikoglu is known to be a hardliner on the PKK.

The Syrian-Turkish confrontation also came in the context of growing concern in the Arab world over the Turkish-Israeli strategic alignment, which Syria has long considered directly aimed at Damascus.

But Syria and Turkey have quarreled for decades over a variety of outstanding issues, of which the PKK is only the latest and, perhaps, developed as a function of Syria’s attempt to counterbalance Turkish dominance in the other areas of rivalry. There are three major questions at issue: Syria’s latent, not actively pursued but not dropped either, claim to the Hatay region, a dispute dating to the pre-World War II era; the very active and important dispute over the waters of the Euphrates and the Turkish Atatürk Dam; and finally, Syrian support for the PKK, now apparently abandoned. (It should be noted, however, that Syria has made similar undertakings before, and that it is by no means certain that the agreement will be honored in full.)

This Dossier examines the varied roots of the Syrian-Turkish rivalry.

Syrians have long claimed their country to be the “beating heart of Arabism”, the cradle of modern Arab nationalism. In the late Ottoman Empire, many of the early theorists of Arab nationalism were Syrian (or Lebanese), and during the Arab Revolt in the First World War, some talented Syrian officers from the Ottoman Army went over to the Arab side. The modern Turkish Republic, the rump remaining from the dismembered Ottoman Empire, borders only two Arab states: Syria and Iraq. Neither border has ever been truly quiet; and of course Turkey now frequently enters northern Iraq in pursuit of PKK Kurdish guerrillas.

Given this history and the geopolitical rivalries of the region, it is perhaps not surprising that Syria and Turkey have a number of areas of disagreement. What is perhaps more interesting is the fact that these disagreements have never led to actual war, though there have been shooting incidents from time to time, aircraft shot down a time or two, and that sort of problem.

Clearly, too, of course, there are not just these immediate causes for quarrel, but geopolitical factors as well: Syria was aligned loosely with the Soviet Bloc in the Cold War while Turkey was in NATO; today Syria is alarmed by the Turkish-Israeli alignment.

This Dossier looks at the major issues in roughly the reverse order in which they appeared: first at the cause of the recent crisis, the PKK issue; secondly at the water issues on the Euphrates, and finally the longstanding, if not terribly active, dispute over the Hatay (Alexandretta).

The Problem of the PKK

The Ba‘ath Party ruling Syria claims to be an Arab nationalist movement. Why would an Arab nationalist movement support a revolutionary Marxist movement of Kurdish separatists, when Arab Syria itself has a Kurdish minority? The answer is not terribly difficult within the context of the Middle East: in all the countries which have Kurdish minorities (mainly Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Syria, though with some in Armenia and Azerbaijan as well), there has long been a pattern of supporting Kurdish movements which destabilize your neighbor, while naturally not encouraging one’s own Kurds in such ideas.

Syria’s quarrels with Turkey stem, as this Dossier seeks to show, from many roots. Of them all, it may be argued that the issue of the PKK is the only one in which the provocation largely originated on the Syrian, rather than the Turkish, side. Syria has used the PKK as an instrument to counterbalance Turkish gains elsewhere. Turkey’s military forces are much superior to Syria, and a conventional military balance is not really achievable, especially with Syria preoccupied with Israel on the Golan Heights.

Syria is not the sole supporter of the PKK. Iraq has also been involved in the past, and today (when the Iraqi government has no control in the north), the PKK has sometimes fought aligned with Jalal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) against Mas‘oud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). Turkey also charges that Greece has maintained training camps for the PKK.

But Syria has been the country whose activities with the PKK most infuriated the Turks. The exact nature of Syria’s support for the PKK depends on which side one chooses to believe. Syria basically denies that it has been a major source of support. Turkey insists that there are training camps in Syria as well as in Lebanon’s Baqa‘a Valley, the latter under the effective control of the Syrian security forces. In addition, “Apo” Ocalan has long lived in Damascus much of the time. Although there have been few, if any, clear instances of operations directly across the Syrian-Turkish border by the PKK (they usually strike from Iraq), Syria’s role in training, supplying, and equipping the PKK has long been alleged by the Turks.

There have also been reports that Syria has sought to encourage its own Kurdish minority to support the PKK, perhaps in an attempt to direct any latent separatism among Syrian Kurds externally.

Under the agreed minutes signed late on October 20, Syria reportedly undertook to close the PKK training camps not only in Syria but also in Lebanon, to bar Ocalan from returning to Syria from his current stay in Moscow, and to prevent all cross-border operations, and cease any logistical, financial, or arms support to the PKK anywhere.

The Turks are trumpeting the agreement as a full Syrian backdown, which, if it is carried out, it would indeed appear to be. On the other hand, Syria has undertaken commitments about the PKK before, only to quietly resume activities when attention was not longer focused on it. It is not impossible that it will do so again.

On the other hand, it must also be remembered that Syria, in backing down under the threat of military strikes, is not really giving up any crucial interest of its own. Like other states with Kurdish populations, it has no intrinsic interest in encouraging Kurdish separatism. Its support for the PKK was always a tactical effort aimed at Turkey, not a committed support of the PKK.

Euphrates Water

If the Kurdish PKK is not a crucial national interest for Syria, water is. Like every other country in this generally arid region, burgeoning populations and limited supplies of fresh water have made water a resource more precious than oil.

And to hear the Syrians and other Arabs tell it, the Turks are trying to turn off the Euphrates. In 1990, in fact, they did virtually that.

The Euphrates rises in eastern Anatolia (Turkey), where its two major component streams come together. It then winds through Syria into Iraq, where it joins with the Tigris to form the Shatt al-‘Arab, flowing into the Arab/Persian Gulf. (The Tigris also rises in eastern Turkey, but enters Iraq directly without passing through Syrian territory.)

The issue of sharing the Euphrates water has always been a contentious one between Turkey and its downstream neighbors, with Iraq, the last in line, generally claiming its share to have been plundered by both Turkey and Syria. When Syria built the big Asad Dam on the Euphrates, the Iraqis complained; naturally, when Turkey began its huge Atatürk Dam as part of its Southeast Anatolia Project (GAP), a master plan involving 22 dams and 19 power plants, both downstream neighbors began complaining anew.

In 1985 Turkey and Syria signed a provisional accord under which Turkey guaranteed a flow of 500 cubic meters per second to Syria. Syria has pushed for a permanent accord, and has continued to complain about the GAP.

The issue of water rights is an extremely complex one, and something of a new cottage industry in Middle East studies. A brief report such as this cannot assess the various conflicting claims of the impact of the GAP on the Euphrates water resources; Syrian and Turkish estimates often differ dramatically.

One of the more delicate moments occurred in 1990 when, to fill the Atatürk Reservoir, Turkey cut off the flow of the River at the dam for a period of 30 days, 13 January-12 February. There was considerable uproar that Turkey was cutting off the Euphrates entirely, but in fact Turkey had not only increased the flow prior to the cutoff, but the cutoff in no way affected the water from tributaries entering the Euphrates below the dam. The Turks also say that the total amount released averaged out, over a period of several weeks, to above the 500 cubic meters a second committed to Syria.

The Atatürk dam and another big dam, the Keban, have their flow regulated by further downstream dams, of which one, the Birecik Dam not far from Syria, is being built currently.As if the water issues were not complex enough, Turkey has counterclaims against Syria concerning dams on the al-‘Asi River, the ancient Orontes, which rises in Lebanon, passes through Syria, and reaches the sea through the Turkish province of Hatay.

And that brings us, like the Orontes, to the oldest of the disputes between Turkey and Syria.

The Hatay

(Sanjak of Alexandretta)

In the extreme northeast corner of the Mediterranean, the Taurus Mountains join the sea, separating Anatolia from the Levant. There, on the Gulf of Iskenderun, lies the port city of Iskenderun (known historically as Alexandretta), and in the mountains inland, Antakya, the ancient city of Antioch. During the Ottoman Empire the region was administered as the Sanjak of Alexandretta. Like most borderlands, it has long been ethnically mixed, Arab and Turkish, with Armenians as well. Historically, Antioch was usually considered a part of Syria, looking inward to the other cities of the Levant, while Alexandretta was a more cosmopolitan port.

In the carving up of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I, France won the inclusion of the Sanjak of Alexandretta in its League of Nations Mandate over Syria-Lebanon. French policy was to maintain separate administrations for ethnic or religious groups with a geographic identity, and thus in addition to Christian Lebanon the Druze mountain of Syria, the ‘Alawite areas around Latakia, and the Sanjak of Alexandretta were given special status.

In the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923, Turkey had renounced any claim to its former territories. But in 1936, when Syria was slated for independence under the mandate, Kemal Atatürk approached France over the question of Alexandretta. Turkey insisted that a majority of its population were Turks, and that it should revert to the Turkish Republic. France insisted that the Sanjak would maintain its own autonomy within independent Syria.

But this was 1936, and France remembered that Turkey had joined the Central Powers in World War I. In an effort to keep Turkey from drifting towards Germany again, efforts were made to accommodate the Turks. The matter was referred to the League, and Syrian independence delayed. In May of 1937 the League recommended an autonomous Sanjak which would control its own internal affairs, but whose external affairs would be under Syria; it would be demilitarized.

Arab nationalists insisted there were 125,000 Arabs, Christian and Muslim, and Armenians in the Sanjak and only 85,000 Turks; the Turks insisted there was a Turkish majority. A French census found a Turkish population of 46%, a minority but the largest single group in the population. Neither side readily accepted those numbers. But France and Turkey subsequently agreed to a Turkish “preponderance” of influence in the region, which in late 1938 elected a Turkish President and renamed itself the State of Hatay.

Since Syrian independence had been postponed, Hatay was technically still under French mandate. In June of 1939, with European war imminent, France signed an agreement on mutual assistance with Turkey and separately ceded the Hatay to Turkey. Turkey took over, and pressured non-Turks who would not accept Turkish citizenship to leave.

Syria has never recognized the incorporation of the Hatay into Turkey. There is still an Arabic-speaking population in the region, though Turks are now the solid majority. Syria does not actively press the claim, and in fact during the recent crisis, Turkish President Süleyman Demirel explicitly warned Damascus not to raise the Hatay issue. On the other hand, Syrian maps frequently show the entire region as part of Syria. (Even Syrian official road maps have been known to do so, doubtless causing confusion for tourists suddenly finding the Turkish border in the way.) Turkey regularly protests the publication of such maps. Though the claim is latent, it has never been renounced by Syria, which holds that France had no right to cede the territory to Turkey under the mandate. When other issues arise between Turkey and Syria, the old quarrel over the Hatay is likely to be resurrected, as Demirel obviously feared might occur this time. †

HERE IS ANOTHER INTERESTING EVENT THAT TOOK PLACE... NATO actually petitioned Turkey to shut off the Euphrates entirely in 1991 according to this writer... Link excerpt:

The Tigris-Euphrates is regularly cited as a flashpoint for a possible war. How can anyone induce Turkey, probably the most powerful state in the region, not to pursue its own interests to the detriment of its downstream neighbours, Iraq and Syria?Everybody keeps talking about the Tigris-Euphrates as a potential flashpoint, but what’s really interesting is that in 1991, Nato actually asked Turkey to shut the flow of the Euphrates towards Iraq. But the government refused and basically said, “You can use our air space and bases to bomb Iraq, but we won’t cut off their water.”

Since the 1970s, Turkey, Syria and Iraq have had an implicit agreement, which Turkey continued to respect even while building the dams. And despite the rhetoric, Syria and Iraq both recognize that they benefit from those dams because they even out the river’s flow and extend their farmers’ growing season. Turkey wants to be seen as a fair, good neighbour for several reasons, including Nato pressure as an ally, internal politics and attempts to join the European Union. The difficulty lies in making the implicit agreements explicit.

“Be not overcome

of evil, but overcome evil with good.” Romans 12:21 In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, any copyrighted work herein is archived under fair use without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in reviewing the included information for personal use, non-profit research and educational purposes only. Ref.

Watchman Bible Study | 2005 - 2025